- NEWS -

NOV 19, 2018

Officials had $1 million for beach access at Hollister Ranch. Where did it go?

By ROSANNA XIA

Mounting public outrage has fueled new efforts by state officials to open a coveted stretch of California coastline in Santa Barbara County. (Tamlorn Chase / For The Times)

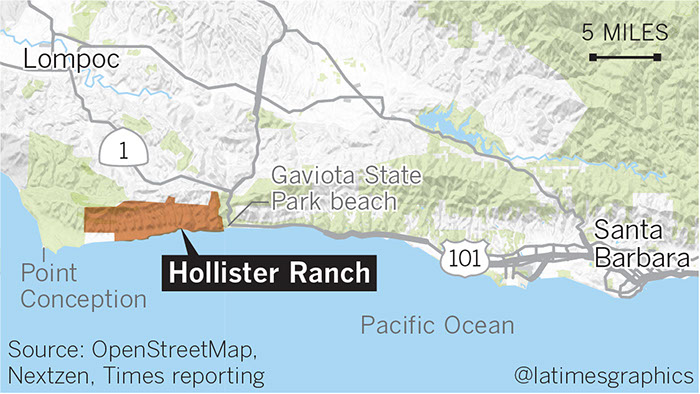

Coastal officials knew decades ago it would take money to open Hollister Ranch to the public.

So they entrusted Santa Barbara County with $1 million to someday be spent on land acquisition, trails and bike paths while they duked it out with powerful property owners over access to some of California’s most coveted surf breaks and beaches.

After more than 30 years of stops and stalls, officials are now gearing up for what might be the most aggressive fight yet over the 8.5-mile stretch of pristine coastline.

But the money was spent long ago on other projects.

“That $1 million would go a heck of a long way,” said California Coastal Commissioner Mark Vargas, when told by a reporter that the county had used the funds.

For so long, Hollister was considered such an imposing force that access to the beach came to be seen as an impossible feat — an attitude that has kept the public locked out all these years.

“‘We can’t beat Hollister, their lawyers are too strong for us, so let's just give up,’ is unfortunately the frame of mind,” Vargas said, “that infested everybody and every agency leading up to … where we are today.”

To reach coveted surf breaks and pristine beaches at Hollister Ranch, many try to boat or paddle along the rugged coastline from nearby Gaviota State Park. (Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

The pipeline gambit

Since the passage of the California Coastal Act in 1976, Hollister Ranch has managed to avoid providing beach access for all.

First, the 14,500-acre ranch got an exception carved into the law allowing it to bypass a requirement that each of its many owners provide a public route to the beach when developing their parcels. Instead the state in 1982 established a plan to implement a ranch-wide access program with walking trails, a bicycle path and a bus.

But property owners continued to push back. Unfettered access, they contended, would undo years of hard work to preserve the ranch’s natural state.

Negotiations went nowhere and the program never got off the ground.

So coastal officials tried a different tactic. The Reagan administration was pushing domestic energy, leading oil companies to seek permits along the California coast.

Chevron USA sought to build a pipeline through Hollister Ranch that would transport oil and gas from offshore platforms near Point Conception to a processing plant east of Gaviota State Park.

FEnvironmental groups appealed to the Coastal Commission, which saw the permit process as a creative way to finally obtain public access at Hollister, records show.

One idea was to require Chevron to establish a strip of land that the public could use to get to the beach.

“Chevron may have the legal ability to provide public access to and along the shoreline across Hollister Ranch property,” the commission said in a report. “As a common carrier, Chevron acts as a public utility.”

Document

"Chevron may have the legal ability to provide public access to and along the shoreline across Hollister Ranch property…. However, the Commission, based on contradictory testimony and the certainty of extensive litigation over any exercise of eminent domain for access by Chevron, finds that such action … is not appropriate in this case."

— Coastal Commission (1985)

The commission ultimately decided this tactic might lead to more lawsuits, further delaying access. When the agency approved the project in 1985, it settled on a different condition: Chevron had to pay $1 million dedicated to implementing a public access program at Hollister Ranch.

Fighting the pipeline was a bitter chapter for Hollister Ranch.

The ranch lost two lawsuits seeking to halt the project. When 28 owners whose properties the pipeline passed through decided to settle with Chevron, “a division developed among owners which took years to heal,” according to a history book published by the Hollister Ranch Conservancy.

An environmental impact review of the project, said Andy Mills, a former ranch manager who wrote the Chevron chapter of the book, “had clearly preferred an offshore pipeline as environmentally safer than an onshore pipeline. The Coastal Commission staff, however, had Chevron pursue an onshore pipeline, hoping to get public access to the ranch as a mitigation measure.”

Coastal commission staff today say that statement contradicts 40 years of policy and just doesn’t sound right. The standard has always been that pipelines are less environmentally damaging onshore than in the water, staff said, because a spill can be better contained on land.

“Whenever possible, wherever feasible, pipelines should be onshore,” said Mark Delaplaine, who manages the commission’s energy, ocean resources and federal consistency division and has worked at the agency since 1976. “That has been a given since we ever started reviewing oil and gas proposals off the coast.”

Construction of the pipeline was completed by 1987, and oil became a part of ranch life. Chimes rang out the first Tuesday of each month to test an emergency siren warning. The scar left by excavation was mulched with straw.

Chevron later sold its interest in the operation to Plains Resources. It stopped transporting oil through Hollister in 2015 after a rupture in an adjoining pipeline spewed crude oil across Refugio State Beach and blackened the sea.

County officials said buried portions of a decommissioned pipeline are typically abandoned in place.

“So we ended up with the worst alternative — the onshore pipeline rather than offshore — and no access,” said Kim Kimbell, who has been a ranch owner since 1974. “But the Coastal Commission did manage to squeeze $1 million out of all this.”

The $1 million

That $1 million went into Santa Barbara County’s Coastal Resource Enhancement Fund, which oil and gas companies pay into each year as a condition of operation. It finances projects such as habitat restoration, marine mammal protection, education programs, coastal recreation and tourism.

The fund has provided more than 300 grants over the years, and the annual allocation by the county Board of Supervisors is a big show of environmental and community groups pitching their many projects for funding.

With so many coastal issues in need of money, and no access agreement in sight with Hollister Ranch by the late 1980s, the county promptly gave away the $1 million to other projects.

Document

"No such public access program has been developed because no agreement has been reached ... Given that understanding, CREF fees collected ... have been allocated to other projects, including other opportunities for new or improved public access to coastal areas."

— Coastal Resource Enhancement Fund (CREF) report

“It’s my understanding that we collected these funds and we never set them aside,” Dianne Black, the county’s planning and development director, told the Board of Supervisors last year. “We immediately allocated them to projects.”

With the fight at Hollister seeming to pick up again after decades of stagnation, Black and her staff, along with the county auditor and lawyer, urged the board to rebuild the $1 million. Fees going into the fund have dwindled over the years as oil operations were phased out — dropping from more than $2 million in 1987, for example, to $414,950 in 2017.

In a charged meeting last June, county supervisors debated just how urgently they needed to come up with $1 million for an access battle that has dragged on so long.

“What we set aside now won’t be spent until 2022 or longer, depending on how competent we think Hollister Ranch’s attorneys are,” said county Supervisor Das Williams, who questioned the opportunity cost “of squirreling away this money” rather than funding the many project proposals before them. “I think they’re very competent attorneys, and they’re going to fight this probably for most of the rest of my lifetime.”

“If something did happen,” said county Supervisor Peter Adam, “and there’s a demand for $1 million, we’re going to have a really difficult time coming up with it.”

So the board voted to set aside for Hollister access $125,450 in 2017, $156,138 in 2018 and another $156,138 to be allocated in February. Similar amounts will continue to be set aside each year until the fund reaches $1 million.

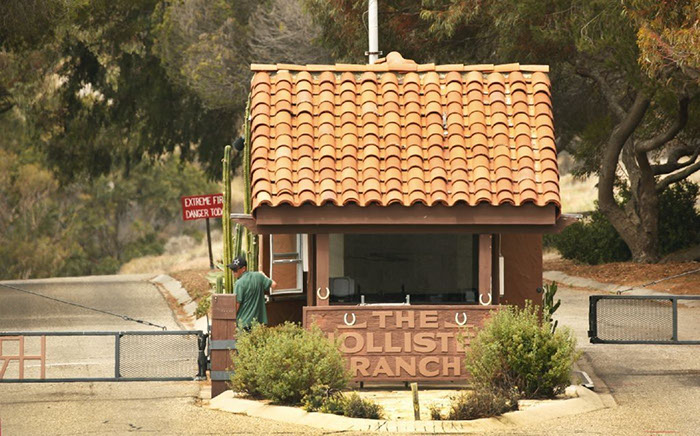

The Hollister Ranch gatehouse guard allows only designated owners and guests to enter the secluded property. (Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

A new push

Access at Hollister had faded from public scrutiny until this spring, when news trickled out that coastal officials had agreed to a deal that barred the ranch’s coastline from everyone but landowners, their guests, select groups and those strong enough to paddle or boat in through treacherous waters.

The state, fielding more than 1,500 emails lambasting the deal, is now looking for ways to finish what it started decades ago.

The latest strategy relies on the access program adopted in 1982. Last month, the Coastal Commission announced it had created a team to update the program as quickly as possible.

“Given the fact that it's going to take a significant amount of funding to implement that plan, that $1 million is a critical part of moving this whole effort forward,” Jack Ainsworth, the commission’s executive director, told The Times.

Several attempts to secure funds for access at Hollister have over the years gone awry.

A separate effort by lawmakers this year to start collecting $1 million for beach access at Hollister was vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown.

Fees collected over the years from ranch owners to fund access amount to $295,000 — though coastal advocates now say that money could’ve added up to more than $1 million had anyone challenged the ranch’s interpretation of how those fees should be paid.

Coastal commissioners are also gearing up to fight any ranchowner seeking new development permits while the standoff continues. And officials at the State Lands Commission have been looking into their own legal authorities, which include eminent domain proceedings, land exchanges or negotiating new boundary lines.

Kimbell, the owner at Hollister, said that careful management is what has allowed the land to heal and thrive. Residents still restrict their own number of guests (12 per parcel per day) and grant access to scientists, historical societies and schoolchildren on occasion.

“We could probably consider expanding some access, but we don’t want to do it to the point that it’s out of the control,” Kimbell said. “The primary purpose of all the owners here is to preserve the beauty of the ranch.”

Susan Jordan of the California Coastal Protection Network, who is pushing for greater access with a coalition of advocacy groups through a court intervention, said the standoff has continued for as long as it has because of the myths and assumptions coming from all sides.

“Nobody wants to run in and trash Hollister Ranch. We all care about the environment,” she said. “There are ways to provide access that are both respectful of private property owners' rights and the environment — and I think it's really time to all sit around the table to figure it out.”

HOLLISTER RANCH 107

- THE CLAVIN RANCH -

- comments -

- HOLLISTER RANCH MAPS -

e-mail: abclavin@yahoo.com

Clavin Family Ranch

113 acres on the California Coast located within Hollister Ranch, a gated community

Santa Barbara County.

For information, contact Jeanette at H&J Properties.

All Rights Reserved © 2024.